Rethinking the Game: AI, Translation, and the Strategy No One's Talking About

Why the Rules Changed, the Players Changed, but Most of Us Are Still Playing the Old Game

AI didn't knock.

It just walked into the translation industry, plugged itself in, and started translating entire websites in seconds for pennies.

Suddenly, translators are wondering if this is the end of their craft. Agencies are under pressure to deliver more for less. Buyers are thrilled to reduce costs. And AI? It's not interested in permission or cooperation, only scale.

But maybe we're misunderstanding what's really happening here.

Maybe this isn't just a story about technology or productivity. Maybe it's a shift in strategy. A shift in the actual game we've been playing: who's in it, what rules apply, and what it means to win.

For that, we need a framework from outside our space: game theory.

What Game Theory Teaches Us

Game theory is the study of how decision-makers interact in strategic environments where each player's choices impact the others. It's not about games in the casual sense. It's about understanding strategic interdependence, risk, and what happens when incentives shift underneath our feet.

It helps explain why cooperation sometimes works, why betrayal sometimes pays off, and why stability is often more fragile than it looks. It's used in economics, war, biology, business, and negotiation. And it has eerie parallels to what's playing out in translation.

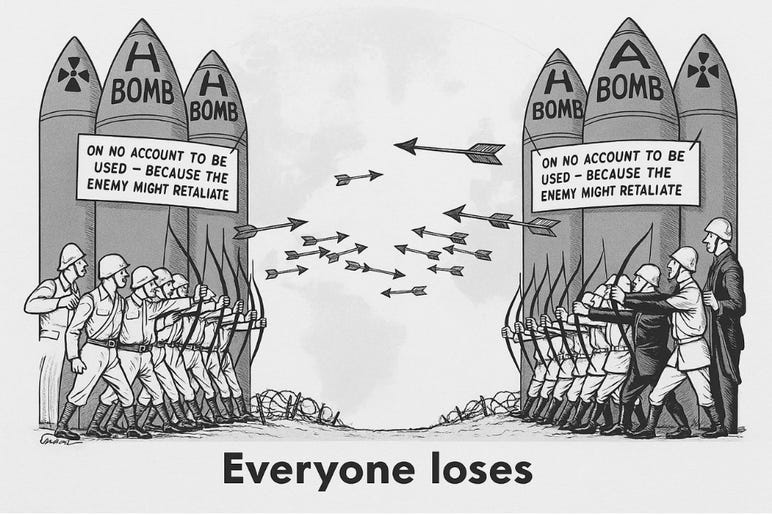

During the Cold War, for example, the U.S. and Soviet Union entered a nuclear standoff shaped by game theory. Each side knew that launching first would invite total annihilation. This created the logic of mutually assured destruction, where neither side attacked because both understood that survival depended on restraint. It was a game where both parties had everything to lose by betraying the system.

Source: https://thecoldwarexperience.weebly.com/brinkmanship.html

In 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world came closer to the brink than ever before. It was a live-action game of brinkmanship—each side inching forward, trying to read the other's move, knowing that a misstep could be fatal. Every action was calculated not just for effect, but for how it would be interpreted by the other side.

Even in everyday life, game theory applies. Remember the infamous toilet paper shortage of 2020? People feared scarcity, so they hoarded. That panic created the very shortage they feared. Each person was acting rationally as an individual, but collectively, the system broke. It's a perfect example of how individual rational actors can create scenarios where everyone loses—a coordination failure that game theory predicts.

These examples might seem far removed from localization, but the underlying dynamics are the same: self-interest, interdependence, fear, and risk. Translation is now full of these dynamics where everyone's actions impact everyone else's.

The Translation Industry's Old Game

For decades, the translation ecosystem functioned as a delicate cooperation game—a strategic equilibrium that kept everyone just satisfied enough to maintain the system.

When machine translation arrived around 2007-2010, it wasn't treated as a revolution. It was an optimization. The industry remained with the same tools, same word counts, same workflows. Nothing really changed from a mechanical perspective. Things were being pre-translated before they were sent out to translators, and because they were pre-translated, agencies could expect to pay less. Translators were expected to work faster.

But even though machine translation was there, buyers and agencies didn't truly rethink their approach. They just pre-filled whatever was going to be translated with machine translation suggestions. This allowed agencies to lower prices slightly, translators to work a little bit faster, and buyers to save.

What emerged was a functional equilibrium—nobody was incredibly happy, but enough people were happy enough to keep the whole thing going. It was almost like there was a silent agreement holding this whole thing together. Everyone gave a little bit of cooperation to keep the system intact.

The lower prices enabled higher volumes. Global expansion was on the rise. Sure, some translators were disgruntled because they were making less, but overall the industry continued to grow. Everyone benefited just enough to keep the model alive.

This was a strategic equilibrium where most players chose cooperation over defection. The logic of the Prisoner's Dilemma applied—players could have acted more aggressively, but most didn't, because the collective outcome was better when everyone played fairly.

A New Player Has Entered the Game

Today, there's a new kind of player, and they're not from inside the industry.

These are AI-native platforms. Not just AI-native platforms, but translation as a feature really getting traction. Tools like Canva offering translation. Translation available in all the Microsoft Office pack. Translation in all of the Google docs and workspace package. Translation available in GPT. YouTube offering translation. Most software out there is offering some kind of translation.

For these players, translation isn't craft—it's data. It's basically understood that for these software companies, translation is a value add using translation, and it's something that's relatively low cost. It increases user experience, adds value, maybe can even justify an increase in a subscription level. Basically, it's all upside for companies that are AI-driven.

They're not agencies. They're not linguists. They don't care about the balance or the nuance. They're treating language as data. That's the definition of translation as a feature—it's not just that it's a feature, it's the treatment of language. It's just data. It doesn't matter if it's good, if it's bad, who authored it, who checked it, whether it represents the brand or doesn't represent the brand. It's just adding something to the user experience.

There's no loyalty to the ecosystem at all. There's only focus on data and scale.

And crucially, they have nothing to lose by destroying value in the system. For them, driving value down to pennies isn't a failure—it's exactly the business model. That is the disruption. It's bringing down something that hypothetically costs 20 cents a word to 0.00002 cents a word.

They're not cooperating. They're not balancing. They're not playing the cooperative game. They're rewriting the game entirely, and most of the industry hasn't realized that the rules have changed.

This distorts the game entirely. The presence of a non-cooperative actor makes the cooperative strategy increasingly untenable. The old moves no longer yield the same results. But many industry players haven't yet realized they're in a new game, or that the rules they're using no longer apply.

The Prisoner's Dilemma, Rewritten

The classic Prisoner's Dilemma plays out when two parties must decide whether to cooperate or betray, without knowing what the other will choose. In this scenario, if both players cooperate, you have okay outcomes. If one defects while another cooperates, then you have a big win for the defector. And if both defect, everyone loses.

In the past, the translation industry (buyers, agencies, linguists) mostly chose cooperation. Everyone benefited just enough to keep the model alive. Margins were adjusted gently. Value was preserved collectively.

But in today's scenario, a third player has entered the room. One with no risk, no shared history, and nothing to lose by betraying everyone else. This new player isn't part of the original ecosystem. They don't share the same risks. They have nothing to lose by betraying everyone else—and everything to gain.

This changes the fundamental structure of the game. When a non-cooperative player enters a cooperative ecosystem, the whole logic breaks down. Strategies that once worked become liabilities.

Why Cosmetic Changes Won't Cut It

So far, the response from within the industry has followed a familiar pattern: surface-level tweaks. Maybe slightly faster quoting, maybe more automated presentation of pricing. Maybe some new UI labels. So now, for instance, maybe the product isn't called translation anymore. Now it's called AI post-editing, or human-enabled automatic post-editing, whatever people call it. It's basically just sprinkling new labels to old things.

But the structure is still intact. What game theory says is when incentives shift, surface changes don't fix the system. It's not just about cost anymore. It's about whether the model even holds.

It’s not about picking one gear over another. It’s about redesigning the transmission.

You can't win a new game with old strategies. Game theory teaches that when the incentives change, tweaks don't fix the problem. They delay the collapse. Trying to preserve the old model with better design is like repainting the walls of a house with a cracked foundation. It looks good. But it doesn't hold.

The Fork in the Road: Three Strategic Paths

Here's where we have a big fork in the road, and there are three different strategic paths available.

Path One: Chase the Disruptors

This is probably what most larger agencies are going to follow, a very aggressive path. You automate everything. You bring rates as low as you can, and you try to survive on speed and volume. You bank on the fact that maybe you were hypothetically charging 20 cents a word, now you're going to go down to two cents a word, but because of that, you're going to be translating so much volume, and it's going to be so automated, overhead is going to be so low, that these agencies are still going to have a significant margin, even operating at a tenth of their cost.

This is the path of racing to the bottom. Strip everything down. Reduce quality thresholds. Prioritize speed, scale, and automation above all else.

Path Two: Defend the Tradition

This is where more niche or boutique agencies are falling, where more traditional agencies are falling: trans-creation agencies. The idea is focusing on quality. This works a lot also in regulated industries. You're protecting rates, and you're figuring out ways to show that quality has value. You're figuring out ways to really sell to clients and decision makers that quality has value, whether because it's protecting the brand, whether it's from legal perspectives protecting the company, whether it's because it's necessary for consumer adoption.

You're really finding ways to keep things the same. Hold the line on pricing. Emphasize craft and nuance. Hope that quality still sells.

Both approaches are understandable. Neither is sustainable in isolation.

Path Three: Design a New Game

But there's a third path that I want to propose, which is not the obvious path. This alternative doesn't reject automation. It uses it—but only where it makes sense.

You use tech to remove friction, not value. And that's something very subtle, but very important. If you automate quotes, if you automate task assignments, if you automate payments, but you preserve the human layer. You automate the stuff that's actually simple, that's actually grunt work, that doesn't necessarily need to be done by a human.

Think about a scenario where a project manager spends 50% of their day literally typing in quotes, inputting numbers in a system. Maybe another part of their day chasing translators that haven't taken their task assignments, emailing people to see how they're doing with their assignments, maybe issuing invoices. All this stuff is relatively low grade. Right now it's typically done by disproportionately high value people. You have high value people doing relatively low grade activities.

What that creates is high overhead, but it also diminishes the value that those people can add to the agency and that the agency can thereby provide to their partners.

If all of a sudden these project managers are no longer doing this heavy lifting of automated high friction things and now they're doing more high value propositions—maybe they're doing more strategic vendor management, maybe they're doing more data-driven quality management, maybe they're doing more relationship building, maybe they're being able to focus more on actual process redesign—all of a sudden you've freed up all of this bandwidth and you've displaced it into much higher value-added bandwidth.

Treating Translators as Amplifiers, Not Obstacles

The next step is treating translators as amplifiers, not obstacles. Instead of looking at the translator as someone who needs to be bypassed or whose work needs to be minimized (and I see a lot of this, especially from enterprises like "we want to make sure that translators touch as little of the content as we can," "we want to make sure that translators generate as little cost as they can"), this is a general mindset where translators are seen as obstacles to cost efficiency.

In my opinion, it's nothing like that. If translators are working in an environment where they're interacting with an AI that is capable of learning from their decisions, of amplifying their decisions, of allowing them to really become guardians of a certain brand voice, of a certain perspective, all of a sudden they become enablers and not just cost drivers. They're enabling a much better performance of content. They're enabling a better experience from the end user. They're enabling brand growth in a certain country.

I think that's always been the dream, but they need the tools to be able to do that. And they won't be able to do that just by being post-editors, just by being reduced to human output managers or what people love to call "humans in the loop" (even though I would never want to be stuck in the loop myself and would never wish that on anybody). It's like trying to reduce people to button pushers.

I don't see translators as that. I see them as immense artists. I see them as cultural guardians for text. And that's my personal perspective, but I see this as immense value. They just need the software, the tools that allow them to do that.

The Challenge of Deep Change

Maybe what I'm proposing is the harder path, and I think it is the harder path because it requires a much deeper reexamination of everybody in the supply chain of what it is that they do. And change is really, really hard.

If you get a project manager, for instance, that was doing quoting and task placement and problem solving all their professional life for the past 20 years and all of a sudden say, "No, you're going to do something different now. Now you're going to do strategic vendor management and you're going to do data-driven quality management," all of a sudden maybe they don't know how to do that. And that's awesome. It's an opportunity to learn. Learning is very uncomfortable. Doing the predictable, doing the same is very comfortable.

Same thing with the translator. If the translator was used to typing all day long and authoring words and all of a sudden they're no longer typing all day. All of a sudden they're assessing text and not just from a pure linguistic perspective. They're assessing text from a cultural perspective, from a market performance perspective. They're working a lot closer to people who actually work for the brand. They're working as product enthusiasts. They're looking at it as a consumer would look at it. They're adding a whole other level of value to their work.

But it's hard. It's not what they developed their career on. I know a lot of translators have incredible methodologies for cross-referencing things in dictionaries and they have exact places where they look online and they have developed these incredible heuristic and mnemonic devices so that they can move very quickly through text. All of a sudden that has very little value in an environment where their worth is all about the value that they're able to add to text that is already good or okay and they're making it great, or they're making it amazing.

This change is really, really hard. And that's why my opinion is that it's not just about trying to do things a little bit differently this time around. It's about time to rethink the game.

Redefining Value and Measurement

This path demands new infrastructure. It doesn't rely on segment-by-segment workflows. It doesn't pay by the word. It doesn't just plug in AI to reduce cost. It re-architects the system so AI can work in service of value, not in replacement of it.

It redefines what value means: not in cost per word, but in clarity, meaning, and outcome. Instead of measuring efficiency by speed alone, it measures impact by brand consistency, cultural resonance, and user experience.

Platforms like Bureau Works are already building for this model. Not as a patch on the old game, but as an operating system for a new one: where tech and talent coexist, where automation empowers rather than replaces, and where translation regains its creative spine.

This path is not easy. It requires rebuilding pricing logic. Rethinking workflows. Reframing how we talk to buyers and how translators think about their work. It demands different pricing, different metrics, different conversations.

But it may be the only path that's both sustainable and worth playing.

Seeing the Game Clearly

Game theory isn't just about answers. It's about seeing clearly. It's about framing the problem in a way that actually makes sense.

Because, in my opinion, this isn't just a faster tool moment. It's a very strategic shift.

The players are different. The rules are different. And the scoreboard is different.

Most companies feel like they're doing a lot more work than they previously did, and they're playing defense. They're doing a lot more work, and maybe they're growing a little bit, but for the most part they're preventing maybe revenue from shrinking. Maybe it is shrinking even with all this work. It's a hard moment for our space.

And that's why my opinion is that you need to ask the bigger questions. What game are we really playing? And what kind of game is really worth winning? These are the kinds of questions that are really going to require people to redefine who they are. And in my opinion, that's probably the hardest question there is: these deeper existential things.

Just by rethinking the game doesn't mean that you're necessarily going to change the game. It means that you're changing the vision for the game.

The Time to Act

The translation world has long assumed the game was stable. That cooperation would continue. That value would protect itself. That the old equilibrium would hold.

But the rules have changed. The players have changed. The scoreboard has changed.

And that means the question isn't "How do we survive?" or "How do we optimize the old model?"

It's: Is it time to stop playing defense and start designing a new game?

When the rules of the game change, survival doesn't go to the fastest or the cheapest. It goes to those willing to see the game for what it is and then design something better.

This is not just another round of optimization. It's a strategic inflection point. A new game, with new players, new stakes, and a very different kind of scoreboard.

The only way forward may not be to play harder, or to resist harder. It may be to stop playing by someone else's rules and start building a game that's worth winning.

Further Reading

Poundstone, William (1992). Prisoner’s Dilemma: John von Neumann, Game Theory, and the Puzzle of the Bomb.

Explores the origin of game theory and its application to Cold War nuclear strategy.Axelrod, Robert (1984). The Evolution of Cooperation.

A foundational work on how cooperation can emerge and survive in competitive systems using game theory.New York Times (2020). How Game Theory Explains the Toilet Paper Shortage.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/business/toilet-paper-shortage.html

A modern, everyday example of strategic behavior under uncertainty and panic.Cold War Museum. Mutually Assured Destruction.

https://www.coldwar.org/articles/50s/mutually_assured_destruction.asp

Overview of Cold War deterrence strategy through the lens of game theory.Slator (2023). Generative AI is Coming for Translation—Now What?

https://slator.com/generative-ai-is-coming-for-translation-now-what/

A look at how the language industry is responding to the rise of AI-powered translation.MIT Sloan Management Review (2021). The New Rules of Competition in the Age of AI.

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-new-rules-of-competition-in-the-age-of-ai/

Discusses how AI alters traditional strategic models and competitive dynamics.Harvard Business Review (2020).How to Play a New Strategic Game.

https://hbr.org/2020/11/how-to-play-a-new-strategic-game

Explores how to adapt when the competitive landscape shifts beneath your feet.

Bravo! And reminder to all that this same sort of “game changer”/changing game is occurring everywhere, in almost every industry, even highly artistic ones. Recognizing how “hard” this is - is kind (and the author is indeed kind!), but irrelevant… Adapting to changing work environments is everyone’s duty - these times are certainly unprecedented and exhausting, which I think fuels this fire of resistance. The need to adapt has never occurred this quickly and consistently, and I feel everyone is simply exhausted, but again solidarity can be found even there. Somewhere this has to break, and I think it will ultimately. Without the ability to move forward on a CLEAR or guaranteed path, I feel the human responses is to quit or resist. Excellent job in stressing the need to see this as an entirely new game, to hit the locker room and regroup.